This phenomenon, which persisted until 1715, coincided with the Little Ice Age, characterized by notably cooler temperatures across the North Atlantic, resulting in harsher winters and shorter summers in Europe.

In 1645, the Maunder minimum commenced, a period of strikingly low sunspot activity

While the cause of the Maunder minimum remains uncertain, scientists acknowledge its connection to the Earth’s climate. Typically, a 22-year span encompasses numerous sunspot cycles, totaling 30,000 to 40,000 sunspots. Yet, during the Maunder minimum’s late 17th-century phase, no sunspots were observed. Although it coincided with the Little Ice Age, the correlation may be coincidental, as the latter began earlier and extended beyond the Maunder minimum. Nonetheless, sunspot activity affects the sun’s brightness.

Consequently, during the Maunder minimum, the sun’s intensity diminished slightly, rendering Earth’s northern latitudes more susceptible to even minor fluctuations in solar output. Given the larger expanse of land in these regions compared to their southern counterparts, temperature variations occur more swiftly. This, coupled with heightened seasonal shifts, magnifies the impact of even minor solar changes, distinct from global trends. While consensus on the Maunder minimum’s link to the Little Ice Age is elusive, a significant and unforeseen connection emerges on a geological scale.

Serbian physicist and astronomer Milutin Milankovitch first highlighted the Earth-sun system’s impact on climate in the 1920s

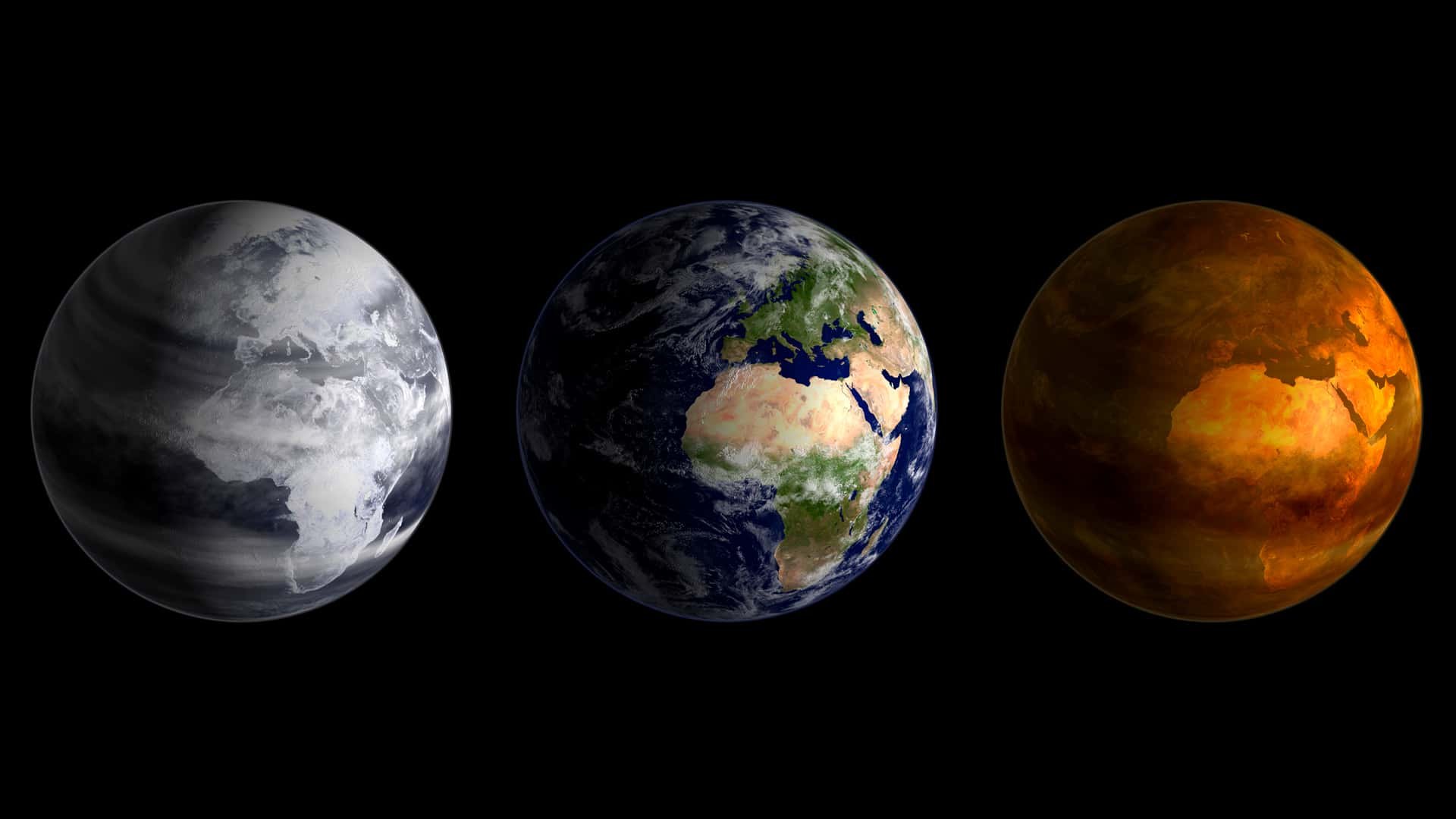

Milankovitch identified three natural cycles influencing Earth‘s orbit. These cycles involve changes in eccentricity, axial tilt, and axial precession, contributing to the length and intensity of seasons. These factors intertwine, sometimes reinforcing or nullifying each other, consistently affecting Earth’s climate. Notably, the Milankovitch cycles align with temperature records from ice cores, revealing a close correspondence between glaciation periods and reduced sunlight in northern latitudes. The last glacial retreat around 12,000 years ago coincided with increased sunlight due to these cycles. Presently, despite expectations of a cooling period according to the Milankovitch cycles, human-induced carbon emissions have overridden this longstanding relationship between the sun and Earth.